Organisational agility – how to knock down structures that are limiting your organisation’s effectiveness.

By Matt Hardy & Dr Marc Levy

Right Thinking

- Organisational agility creates value – agile organisations dramatically outperform unadaptive organisations

- An agile organisation is agile in strategy, ways of working and resources

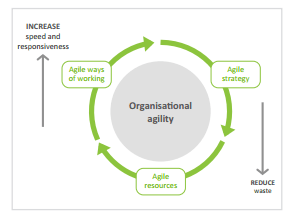

- These three agile levers, used together, can not only increase speed and responsiveness but can also reduce waste

The following is extracted from the full white paper, which can be found here – View PDF

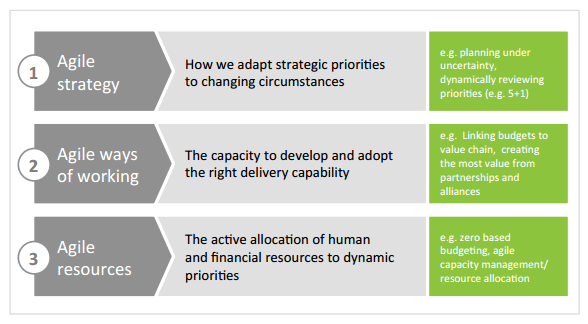

At Right Lane, we think that organisational agility can be simplified into three agile levers:

- Agile strategy

- Agile ways of working

- Agile resources.

Used together, the three forms of agility can not only increase speed and responsiveness but also reduce waste (see figure 1 below).

Let’s briefly look at each of these agility levers, starting with what each lever means, addressing questions to diagnose your own agility for each lever, and then considering some potential tools to create value.

Figure 1: Organisational agility

Agile strategy

We define agile strategy as how we adapt strategic priorities to meet changing circumstances. It starts with understanding when, how and in what way the competitive circumstances have changed – or are changing – and then understanding how to adapt the organisation’s priorities accordingly.

The shift required for many organisations is from old to new thinking, from conceptualising their circumstances in one way to another: organisations cannot necessarily rely on existing strategic settings and historical sources of advantage to deliver the success they once did.

Similarly organisations cannot rely solely on the traditional strategy and planning processes such as annual strategy retreats and fixed planning cycles. The shift is on from these static approaches to strategy and planning to more dynamic, active management of priorities.

We believe that organisations need a balanced approach between maintaining clarity of direction and the agility to see and seize game-changing opportunities, and that these are not mutually exclusive themes. We also believe organisations will need to become comfortable, and competent, with a more active and iterative approach to setting and shaping priorities.

Some questions to consider

How well does your organisation:

- constantly endeavour to ‘see’ things emerging or on the horizon that will have an impact?

- deeply understand the key assumptions underlying its strategy and the triggers or early warning signs for these assumptions?

- translate research into insight, insight into implication, and implication into action?

- ensure visibility of the make-up and progress of the overall portfolio of projects, not just the individual projects?

- prioritise the important and the urgent?

- ensure everyone’s individual priorities are directly linked to their manager’s priorities, in a way that doesn’t feel like micro-management?

Tools and approaches

A tool we’ve used to help organisations make strategic decisions in uncertain conditions is strategic pathway planning (or planning under uncertainty). We’ve found that scenario planning exercises don’t amount to much. Frequently they result in well conceived, engaging scenarios, but from a planning point of view they don’t always improve the chances of your organisation being practically prepared for different market place eventualities.

Instead, consider a small number of alternative pathways, which are combinations of likely, material external and internal developments that are clearly related; that is, likely to happen together (for example, a product development and competitive response, a regulatory change and a business model transformation). Then consider ‘no regrets moves’. What can you get on with now that is sensible irrespective of the eventual strategic pathway. And what are the longer term shaping moves you can make to anticipate pathways and react to them as signs emerge that they are unfolding.

Dynamically reviewing strategic priorities is an obvious agile strategy tool, but in our experience it’s rarely done consistently and well. Strategic moves and competitive responses are unlikely to always fit neatly into strategic or business planning cycles. For some clients this has been a shift in mindset and for others a change in practice. Either way, a rigorous and continuous focus on what really matters strategically, on acting quickly, on slaying sacred cows (and having the conversations required to do so) requires courage and discipline.

We have also found that organisations benefit from a basic 5+1 approach to determining priorities at an individual level (Bregman 2013). Here a leader identifies their five things of major focus for the upcoming period (say the next quarter), which should account for 95% of their attention, time and energy and all ‘other’ things together can only take the remaining 5%. This 5+1 approach is then considered in turn by each executive and their reports and so on. Done well it provides outstanding focus, transparency and alignment.

Can you all agree on the five priority activities for each executive over the next three months and how much time they should allocate to those activities?

Successful organisations, and leaders, are disciplined and dynamic, and know why, when and how to pull the right lever, and to get others pulling the same lever.

Agile ways of working

We define agile ways of working as the capacity to develop and adopt the right delivery capability, taking into account internal and external skills and relationships, to best achieve an outcome for the opportunity at hand.

For example, organisations can become more agile by taking a more open and fluid approach to reviewing and developing the capacity, quality and potential of relationships. The tools for success include identifying which relationships have the capacity to make the biggest difference (positive or negative) and then working collaboratively to seize the biggest opportunities or combat the biggest risks or threats.

Some questions to consider

How well does your organisation:

- understand the relative cost in time and money of its different business activities, across organisational functions, and the extent to which these activities create competitive advantage?

- identify when and how best to use external resources?

- create the most value from its partnerships and alliances?

- develop quality relationships between its disciplines, divisions, and teams?

- identify and develop new relationships or collaborations across its networks of suppliers, distributors or customers?

Tools and approaches

Conducted regularly, value chain analysis can promote agility. As circumstances change, organisations should revisit where they add distinctive value and where others do it better. Value chain analyses, which plot the end-to-end delivery process in an industry the way customers experience it, offer a classical tool for determining where you want to focus, how you want to add value and where you want to have someone else (better, faster, cheaper) do it for you. Our clients are reviewing these decisions more frequently and with increasing rigour, particularly with respect to sourcing decisions.

Another tool that can provide insight relates to assessing and improving partnerships and alliances. We use an approach called ‘alliance strategy mapping’ (adapted from Kaplan, Norton & Rugelsjoen 2000). This is a way of developing and managing relationships with suppliers, alliance partners, or even other teams within the same organisation.

It is a shift from managing by operational metrics and service level agreements to focusing on strategy, commitment and results. It includes using independent experienced facilitators adapting some of the principles of professional mediation to engage, interview and hear from all parties before bringing them together. The facilitators then help the parties deliver a structured, facilitated, tailored workshop to agree and commit to an alliance strategy and establish a new rhythm for the partnership.

Align and realign with your key service providers frequently. They are delivering important business processes for your organisation and their imperatives need to reflect your – flexible – imperatives. SLAs that are revisited annually and re-negotiated even less frequently are unlikely to promote the kind of agility your organisation wants.

Agile resources

We define agile resources as the active allocation of human and financial resources to dynamic priorities.

This may require a shift in operating model; for example, moving away from the inflexibility and inertia of annual budgets being allocated within an inch of their lives, to budgets that can be quickly re-shaped or re-directed to meet new environmental realities or opportunities.

The challenge is to increase flexibility without just adding cost. This involves: taking a disciplined and sharper focus on the reality of each department’s key activities; establishing what is absolutely ‘must do’ activity and identifying discretionary activity for what it is (unfunded unless there is a sound rationale to keep doing it); and creating ‘thin’ budgets, allowing more flexibility of funding allocation and timing.

There needs to be sufficient funds after spending on the ‘known’ to allow for discretionary spending, providing scope to test or trial possible game-changing innovations.

Some questions to consider

How well does your organisation:

- effectively manage the resourcing of both ‘now’ and ‘new’?

- quickly move resources and focus from one area to another?

- extract itself from areas of diminishing reward or advantage?

- commit focus, funds and resources to areas of promise?

- quickly undo existing projects, organisational silos and operational processes and re-direct budgets and resources, when necessary?

Tools and approaches

Tools that can create value include agile approaches to financial and human resource allocation. These include ‘zero-based budgeting’ or key value driver budgeting, and creative forms of capacity management such as using professional services firm staffing disciplines for the delivery of strategic projects.

First, let’s examine agile approaches financial resources. Annual budgeting processes frequently start with last year’s numbers, unchallenged; it is assumed that expenditure from the previous year should be maintained at similar or higher levels. But things change, within organisations and within the environments in which they operate. Budgets need to reflect the flexible, agile plans that management should adopt in response to those changes. This may mean building the budget from scratch, or at least the discretionary parts of it (generally most of the budget), and constructively challenging resource allocations. You might have a more rigorous executive team prioritisation discussion this year (where you are forced to make choices) or invite in external experts to discuss how they’d be allocating your budget based on what they know about the way the industry is changing. It can also mean reviewing the budget and reallocating resources more frequently during the year.

It might be that there is scope for a level of budgeting detail between the top line budget on a page, which can hide a multitude of sins, and the 20-sheet budget booklet, which is so detailed that people only interrogate their own numbers. Would making the five to ten key budget lines from each team’s budget – along with the organisation’s major cross functional project slate – encourage more open debate about the way the organisation is spending its money?

Analyse the last three years’ budgets. Where are the numbers inert; that is, not moving up and down to reflect the changing needs of the business? Where is there an even upward trajectory of 3-5% increases every year? Does that resource allocation make sense given what is known about the opportunities and challenges facing the industry and organisation?

To foster agile financial resources, we also suggest more forward looking budget meetings. What’s changing? What does that mean for what we should prioritise in the next quarter? How can we free up resources and allocate them to where there is the highest need (urgency/ importance)?

Create a fund for ad hoc investment requirements. Increasingly, key business issues crop up during the year, and don’t fit neatly into annual budgeting cycles. Some of our clients have isolated investment funds for this purpose. Such a budget allocation, which executives need to pitch to a committee to access, should have rigorous requirements but should not be overly bureaucratic. Properly set up, such an investment fund can help to limit the contingency that executives are otherwise incented to build into their annual budgets.

Now let’s examine agile approaches to human resources. Within your organisation, are the right people doing the right things at the right time? As a project-based enterprise, we think about this challenge at least every week, as people come off projects and new projects get started. It’s perhaps easier for us than for an organisation that is a mix of ongoing operational work and projects, like most of our clients; because of the natural turnover in our project work, we can be very flexible with resource allocation. If someone isn’t busy enough we can add another project to their work program. If they are doing too much, we can choose not to staff them on new projects for a month or two, or we can reallocate some of their work to a colleague with similar skills who is under-utilised. If they are not developing as fast as we would like in a certain area, we can look to staff them on the next project that is likely to give them that development opportunity.

This is harder for some of our clients because of the mix of their work, and sometimes because there are (frequently understandable) industrial barriers that impede more flexible resource allocation. However, there are some things that all organisations can and eventually will do. These include: more deliberately identifying and predicting the resourcing needs of forthcoming project work; knowing what knowledge and skills your people can bring to the work of your organisation; and identifying under and over utilisation and managing it, including by staffing people, from whichever part of the organisation they come, onto suitable projects.

Expand the pool of resources available to staff projects on short notice, by better understanding the knowledge and skills of your people. At one of our clients, a member of the investment team has become a highly desirable resource on strategic marketing projects because of his analytical capacity and sound commercial judgment. That’s good for the organisation and good for him as it makes his role more interesting and adds to his professional development experience. For most organisations, staffing projects more flexibly is contingent upon having an accurate view of what projects are coming up and their likely resourcing requirements.

Figure 2: An organisation can be agile in strategy, ways of working and resources

Conclusion

Organisational agility creates value and can not only increase speed and responsiveness but can also reduce waste. An agile organisation is agile in strategy, ways of working and resources. And as with human physical agility, organisational agility can be developed and matured.

So you owe it to yourself, and your organisation, to look at your current and potential capacity through an agility lens.

Here is a consolidated list of tips for doing so:

Agile strategy

- Keep abreast of alternate strategic pathways

2. Dynamically review strategic priorities

3. Evaluate senior management priorities and time allocation

Agile ways of working

4. Know where you add distinctive value and where others do it better

5. Align and realign key service providers frequently

Agile resources

6. Foster transparency in financial and human resource allocation

7. Fight resource allocation intransigence

8. Create a fund for ad hoc investment requirements

9. Reallocate resources more frequently, as necessary

10. Staff projects more flexibly.

It’s also important to review and learn. Perhaps ironically, agility can take years to get right. That doesn’t mean that you can’t access dividends from it rapidly; rather, your organisation needs to keep working at it and continuously improving your approach. In the recent past, what resource allocation decisions worked and what didn’t? Where were we agile and where were we too slow to move? What can we do better?

We can see, in our everyday lives, how agility makes a difference. Can you see the opportunity within your organisation?

Note: Some of these ideas were adapted from Birshan, Engel & Sibony (2013)

References

Birshan, M, Engel M & Sibony O 2013, ‘Avoiding the quicksand: ten techniques for more agile corporate resource allocation’, McKinsey Quarterly, October

Bregman, P 2013 ‘A personal approach to organisational time management’, McKinsey Quarterly, January

Casler, C, Zyphur, M, Sewell, G, Barsky, A, Shackcloth, R 2012, ‘Rising to the agility challenge, Continuous adaptation in a turbulent world’, PricewaterhouseCoopers and the University of Melbourne, September

Glenn, M 2009, ‘Organisational agility: How business can survive and thrive in turbulent times’, Economist Intelligence Unit, The Economist, March

Kaplan, R, Norton, D & Rugelsjoen, B 2000, ‘Managing alliances with the balanced scorecard, Harvard Business Review, January-February

Reeves, M, Love, C, Mathur, N 2012, ‘The Most Adaptive Companies 2012, winning in an age of turbulence’, The Boston Consulting Group, August Sull, D, 2009 ‘Competing through organisational agility’, McKinsey Quarterly, December

For more information contact Dr Marc Levy at marc@rightlane.com.au

© 2014 Right Lane Consulting