Digital strategy

Digital directions: Themes from the management literature

Dr Marc Levy and Andy Baker – December 2014

View PDF

Digital strategy is an increasingly important agenda item for most organisations. In this article, we review insights from the best literature to help our clients navigate this challenging terrain.

‘Digitisation is re-writing the rules of competition, with incumbent companies most at risk of being left-behind’ (Hirt & Willmott 2014).

If your company doesn’t offer a great digital experience, many customers, particularly younger people, will move to industry competitors or do more with companies…that offer great customer experiences digitally…’ (Weill & Woerner 2014).

Intimidating quotes like these abound in the literature on digital strategy. As do startling performance data like these:

‘Those businesses in our study that had a strong Digital IQ…were 2.2 times more likely to be top performers in revenue growth, profitability and innovation’ (PwC 2014).

At Right Lane, we’ve been grappling with these questions: What are the major emergent themes in the quality management literature on digital? Do the dominant strategy frameworks work in the digital economy? How should our clients engage with digital disruption? What should they do? What are the major opportunities presented by digital? What questions should executives ask their internal teams about their digital initiatives? What governance and organisation models are appropriate? What tools can clients use to help navigate the digital future?

We plan to include our perspectives on these different questions in this and forthcoming issues of Right Lane Review, along with insights gained from our recent ‘digital economy’ study tour to the US, including a three-day intensive at Boston’s Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). In this issue we focus on common themes in the literature; we have identified seven of them, ranging from rates of adoption to digital marketing. We start with one of the biggest themes: How does digital impact a classic model of competitive rivalry?

Competitive rivalry

‘Smart, connected products will substantially affect structure in many industries, as did previous waves of internet-enabled IT’ (Porter & Heppelmann 2014).

Michael Porter, author of the Five Forces model of competitive rivalry, wrote recently that digitisation has the capacity to fundamentally reshape industry structure. Dramatically expanded opportunities for product differentiation, changes in the relative power of supply chain participants, changes in the mix of fixed and variable costs, and changes to traditional industry boundaries all contribute to a rich and challenging set of new strategic choices for firms in industries from aviation, to agriculture, sporting goods, financial services, energy, fast moving consumer goods and others.

Porter’s case is that the rules of competition have not changed – internal rivalry, threat of new entrants, buyer power, threat of substitutes and supplier power remain the key drivers of industry structure. However, changing product possibilities and shifting economics of production are changing the dynamics within industries and the definition and boundaries of many industries.

Porter’s analysis neatly encapsulates the challenge for many of Right Lane’s clients, whom we are assisting to not only digitise their own internal businesses operations and customer interactions, but also to look at how digitisation will change the structure of their industries and their competitive positioning both now and in the years ahead.

Rates of adoption

‘Today many industries – all moving at different rates – are shifting towards a digital world of “space: more intangible, more service-based and oriented toward customer experience” … Industries will follow – at different paces, driven in part by issues such as regulation, product complexity and how amenable the products are to digitisation’ (Weill & Woerner 2014).

We are seeing materially different rates of adoption across the different clients and sectors we serve, driven as much by consumer behaviour and competitive intensity as the factors referred to in the quote above. In financial services and healthcare, for example, some incumbents have found it challenging to reimagine the customer experience, and many attackers have found it difficult to disrupt powerful legacy distribution systems. It seems to us like we are close to tipping points in both sectors and this is exercising the minds of our clients. How long will trusty sales and marketing methods predominate? How should they allocate resources between (proven but diminishing) wholesale and (highly prospective and emerging) retail distribution, when it is challenging to predict the impact of the latter?

We are recommending to clients carefully constructed experiments for new channels and more dynamic initiative prioritisation and resource allocation.

Big data

‘The digital technologies underlying their competitive thrusts may not (all) be new, but they are being used to new effect. Staggering amounts of information (is) accessible as never before, from proprietary big data to new public sources of open data. Analytical and processing capabilities have made similar leaps …’ (Hirt & Willmott 2014).

Our clients are rapidly evolving their business intelligence (BI) functions to drive more business value. BI teams’ roles have been transitioning for some time – from internal reporting on operational trends and the competitive environment to more sophisticated marketing applications that anticipate existing and prospective customers’ behaviour. This trend is intensifying as the tools improve and organisations get a better sense of where big data can add the most value.

Big data is not all about BI functions obviously. With more and better data, our clients are working on improving the way they gather and use data to support strategic thinking and strategic planning right across their organisations. For example, they are identifying ‘weak’ environmental signals that might validate or invalidate their key business assumptions or predict favourable or unfavourable movements in important business drivers. Clients are also improving the way they organise around data. This has been too fragmented and inconsistent in our experience and that is changing.

Cost reduction

‘Digitisation transforms global flows by vastly reducing marginal production and distribution costs in three ways: … (creating) purely digital goods … (enhancing) the value of physical flows by the use of “digital wrappers” that pack information around goods …, (and) creating online platforms that bring efficiency and speed to production and cross-border exchanges’ (Bughin, Manyika & Nottebohm 2014).

A client said to me recently that in his sector, the legacy service model was a horse and cart racing a new economy sports car. The way customers want to be engaged (less face to face, more digital) was evolving quickly, and he wanted to accelerate the attendant service model changes and bank the efficiencies. But the team was naturally reluctant to make the transition. The old model had been highly valued by customers and had driven good business outcomes. Of course there was a level of anxiety about what the new business model might mean for their jobs and those of some of their colleagues.

This is far from an isolated case. It highlights some of the complications in transitioning business models, and the metaphor underscores the potential consequences of not doing so.

Complexity

‘… Many companies are stumbling as they try to turn their digital agendas into new business and operating models … digital transformation is uniquely challenging, touching every function and business unit while also demanding the development of new skills and investments that are very different from business as usual’ (Olanrewaja, Smaje & Wilmott 2014).

Digital business models can be blissfully simple, but more frequently in our experience they can be complex and challenging, particularly for incumbents. Many of our incumbent clients are struggling with where they should focus their efforts – product, service or marketing – and how they can engage customers to help direct their choices. Digital is burning a hole in budgets, sometimes supported by a great leap of faith about prospective impact.

How can this risk be mitigated? We recommend asking some of the following questions of senior officers with responsibility for digital:

- How will digital impact our existing business model? What is our digital business model? Are the two things the same?

- How does our organisation create value digitally now – through content, customer experience and/or platform? Which of these three do you expect to be most important in three years time (Weill & Woerner 2014)?

- What should we prioritise, considering – for example – the relative importance of goals relating to revenue creation, customer experience, efficiency and flexibility?

Organisation

‘The most progressive organisations are learning to be like the web – they distribute digital staff across key departments, with a core group of experts that lead key initiatives, set up frameworks, and connect the dots while supporting others to lead’ (Mogus, Silberman & Roy 2011).

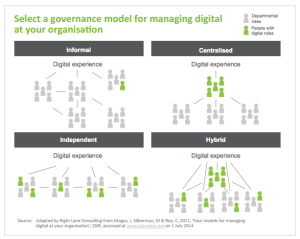

How should we organise for digital, where and how should this new capability report? We have seen the emergence of several models, well reflected in the following chart (Mogus, Silberman & Roy 2011), delivering varying degrees of success.

Another organisation challenge occupying the minds of our clients is, ‘Which positions to fill first?’ Many of these positions have new names, and the knowledge, skills and abilities to make a success of them are different from conventional positions: digital strategists, experts in mobile customer technology, social media specialists, content developers, omnichannel marketers, CDOs, user experience designers, data scientists and so on. Which roles will be most important for your organisation and in what sequence? Will you consider ‘acqui-hiring’?

Digital marketing models

‘There are four equally successful digital marketing models: digital branders (focus on building and renewing brand equity and deeper consumer engagement); customer experience designers; demand generators; and product innovators (use digital to build new products and services)’ (Egol, Peterson & Stroh 2014).

The typology referred to in the quote appears comprehensive. However, in our view, customer acquisition (demand generation) and activation are key skills for all organisations, and are generally given insufficient focus in the digital literature. A ‘build it and they will come’ attitude is (usually) misguided; that is, there is not much content that is so compelling nor many digital experiences that are so captivating that customers flock to them without demand stimulation.

We’ve found that the customer acquisition and activation dimensions of digital marketing are far too frequently overlooked, or deemphasised, when – as in most business domains – they are the most important factor. And digital marketing is a completely new marketing competency. We know great marketers, steeped in old economy demand creation experience, who are at sea in the digital economy. It’s a different language, with different tools and approaches: a solid theory on what drives the Google algorithm is as important as insight about the allocation of resources across the marketing mix.

Digital does appear to be changing almost every industry and we trust we can continue to share insights with our clients that help them navigate this new terrain.

Want to know more?

If you would like a copy of our digital knowledge module or if you would like Right Lane to help you understand how digital can influence your strategic thinking, contact us today.

Download the Right Lane Review

References

Bughin, J, Manyika, J & Nottebohm, O 2014 ‘How digitization is reshaping global flows’, McKinsey Quarterly, May

Egol, M, Peterson, M & Stroh, S 2014, ‘How to choose the right digital marketing model’, Strategy+Business, Summer Issue 15

Hirt, M & Willmott, P 2014, ‘Strategic Principles of competing in the digital age’, McKinsey Quarterly, May

Mogus, J, Silberman, M & Roy, C 2011, ‘Four Models for managing digital at your organisation’, Standford Social Innovation Review, 13 October

Olanrewaja, T, Smaje, K & Wilmott, P 2014, ‘The seven traits of effective digital enterprises’ McKinsey Quarterly, May

Porter, M & Heppelmann, J, 2014, ‘How smart, connected products are transforming competition, Harvard Business Review, 2014

PwC, 2014, ‘The five behaviors that accelerate value from digital investments’, March

Right Lane, 2014-11-14

Weill, P & Woerner, S 2013, ‘Optimising your digital business model’, MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring, pp. 71-78

Weill, P & Woerner, S 2014 ‘Engaging your customers digitally,’ Revitalizing your digital business model conference, Boston, 15 July 2014

Egol, M, Peterson, M & Stroh, S 2014, ‘How to choose the right digital marketing model’, Strategy+Business, Summer Issue 15

Hirt, M & Willmott, P 2014, ‘Strategic Principles of competing in the digital age’, McKinsey Quarterly, May

Mogus, J, Silberman, M & Roy, C 2011, ‘Four Models for managing digital at your organisation’, Standford Social Innovation Review, 13 October

Olanrewaja, T, Smaje, K & Wilmott, P 2014, ‘The seven traits of effective digital enterprises’ McKinsey Quarterly, May

Porter, M & Heppelmann, J, 2014, ‘How smart, connected products are transforming competition, Harvard Business Review, 2014

PwC, 2014, ‘The five behaviors that accelerate value from digital investments’, March

Weill, P. & Woerner, S, 2013, ‘Optimising your digital business model’, MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring, pp. 71-78