Three levers for enhancing your organisational network

by Dr James Mills & Linda Deng

Right Thinking

Organisations can be considered as networks of individuals connected though an intricate web of reporting lines, functional links and interpersonal relationships. At the most fundamental level, it is the optimality of this network that determines an organisation’s ability to deliver on its strategy, to out-operate the competition and, ultimately, to win in the market.

In our work helping organisations to develop and execute winning strategies, we often witness the dramatic changes that leaders can affect within their organisational network through a combination of three different levers:

1. Reconfiguring the macroscopic structure

2. Enhancing connections

3. Enabling self-regulation.

Something is not quite right. Your leadership team has aligned on an ambitious strategy and your organisation boasts some of the most sought after talent in the industry. You have the proven capabilities required to deliver on your strategy and yet something is holding you back.

When faced with this situation, a natural response is to ask whether your organisational structure, ways of working and/or culture are fit for purpose. But how can you identify the peccant element? If this is a question you’ve been pondering recently, then perhaps it’s time to take a closer look at your organisational network. Organisational network analysis is a powerful tool that can help leaders identify structural conflicts and uncover opportunities to develop more effective ways of working and enhance cross-functional collaboration.

Since large organisational networks can be incredibly complex, analysing and interacting with them can seem a daunting task. Inaction, however, can prove costly. Organisational networks evolve over time and, if left untended, often become ineffective or dysfunctional. On the other hand, leaders who truly understand their network can leverage it to align the organisation’s operations with its strategy, drive organisational change, and enhance operational effectiveness.

Understanding effective networks

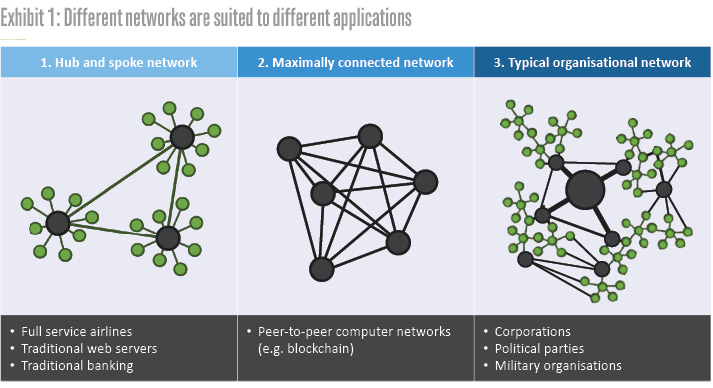

Different networks are suited to different applications. For example, full service airlines operate a ‘hub and spoke’ network of flights. Their fleets are based in centralised hubs and they offer direct flights to nearby airports while longer distance flights ‘connect’ through other hubs. This allows services such as end-to-end baggage transfers to be handled efficiently at the hubs. In the 1990’s the low fare carrier Southwest Airlines famously disrupted the industry by employing a radically different point-to-point network of flights.

Similarly, an organisational network must be fit for purpose. Naively, one might assume that the ideal organisation would be a maximally connected network in which each pair of individuals share a direct connection; this would resemble a peer-to-peer network in computing.

People however are not like computers. In practice, there is a limit to the number of close connections we can maintain. Recognising this, large organisations have long been divided into smaller collaborative groups. For example, in the Roman army a ‘contubernium’ of eight men (a precursor to the modern day squad or section) would march, camp and fight together.

An effective organisational network need not therefore be maximally connected and in practice, there are diminishing returns from building connectivity between individuals at opposing edges of the network. What matters is how centralised or decentralised the network is, where the most influential nodes are located and the strength of connections between groups within the network.

Affecting change within your organisational network

In our work helping organisations to develop and execute winning strategies, we often witness the dramatic changes that leaders can affect within their organisational network through a combination of three different levers:

- Reconfiguring the macroscopic structure

- Enhancing connections

- Enabling self-regulation.

1. Reconfiguring the macroscopic network structure

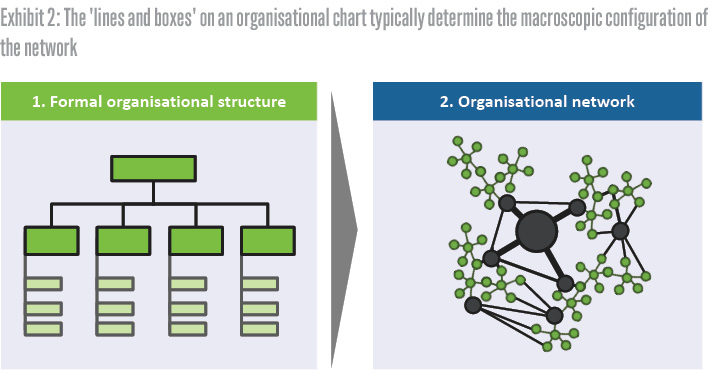

Leaders do not have perfect knowledge of the complex web of relationships that exist within their organisation. Even at the executive level, the relationships between peers do not appear on an organisational chart. Furthermore, the connections that are captured correspond only to reporting lines and encode no information about the quality of the relationship between individuals; that is, how effectively they communicate, their level of mutual trust, etc. Nevertheless, formal structures such as the ‘lines and boxes’ on an organisational chart typically determine the macroscopic configuration of the network* (See exhibit 2).

*The macroscopic configuration is the high-level structure of the network. Typically this reflects departmental or geographical groupings.

It is common for the fine structure of the network to depart from the organisation’s formal hierarchy. However, at the macroscopic level, lack of alignment between the formal organisational structure and the spread of influence across the organisational network can become a significant source of friction. We recently worked with one organisation where the business owner held no formal leadership role and yet commanded significant influence throughout the business. The ensuing conflict of influence obfuscated roles and decision-making rights hamstringing the organisation’s productivity.

The primary nodes of the network are the main conduits for information flow between different functional teams. Weak links between these nodes can therefore severely limit internal collaboration. Therefore, for an organisational network to function effectively, in addition to ensuring the ‘lines and boxes’ on the organisational chart reflect the organisation’s operations, it is necessary to get the right names in each box, thereby facilitating collaboration and efficient information sharing across the team.

2. Enhancing connections

In some cases, leaders may wish to take direct action to enhance the strength of network linkages. There are a number of approaches for doing so, many of which we have discussed in detail in previous Right Lane Review articles (Diego 2017, Hardy & Mills 2018, Pappas & Cossens 2018).

One practice that we have observed to be particularly effective for enhancing connections across an entire organisational network is to engage in a refresh of the organisation’s core values. Crafting ‘aggressively authentic values’ (Lencioni 2002) and articulating the specific behaviours that characterise them can act to ‘reset the bar’ for collaboration and communication across the network.

Reciprocally, leaders can leverage their organisational network to affect cultural change within their organisation. By conducting an organisational network analysis for example, leaders can identify influential nodes within their organisation and appoint ‘culture champions’ to help articulate and embed these ideas across the organisation (Diego 2017).

Following an organisational network analysis, leaders may also seek to build or enhance connections between specific regions within the network. One-off social events are notoriously poor at building these connections as cliques typically form around established collegial relationships. In contrast, regular social and professional interactions, or better yet, opportunities to collaborate on projects that generate mutual value, can help build strong interpersonal connections.

At Right Lane we therefore think of the linkages within an organisational network as crossing a spectrum from ‘coffee’ to ‘collaborate’. One approach that we advocate for building cross functional connections as you mobilise your strategy is to assemble a ‘team of teams’ to identify your organisation’s ‘quarterly best next steps’ (Hardy & Mills 2018).

3. Enabling self-regulation

As staff members make new connections, change roles, leave or join the organisation, the network continually evolves. Actively managing this living system is an arduous task. However, once an effective macroscopic structure is established and effective ways of working have been embedded, leaders can take steps to encourage their organisational network to self-regulate.

Establishing parameters that passively reinforce important connections is key to enabling self-regulating behaviour. For example, creating rigorous measurement, monitoring and review processes reinforces trust along reporting lines. To bolster interdepartmental peer-to-peer connections, one of our clients now regularly holds joint departmental meetings. In another organisation, two departments were co-located to remove barriers to communication that had previously inhibited collaboration.

[testimonial]

The coordination – collaboration trade off

In his book ‘Team of Teams’ General Stanley McChrystal highlighted that, in general, a trade-off exists between centralised organisational networks in which power is held at a few key nodes and highly distributed networks in which power is divided between all individuals. The former allows centralised decision-making to result in highly efficient coordinated action across the network whereas the latter allows nimble localised decision-making and greater collaboration. For most organisations a balance between coordination and collaboration (between centralisation and distribution) must be struck.

[/testimonial]

Our approach to engaging an organisation network

At Right Lane we believe that analysis should always be purpose driven. While a deep organisational network analysis can certainly yield valuable insights about an organisation, a comprehensive network analysis is a significant undertaking and may not always be the most appropriate approach.

We recommend that our clients consider an incremental, three step approach to engaging with their organisational network.

Step 1: DEFINE precisely the insights you are seeking. For example, you may want to highlight opportunities for collaboration, identify information bottlenecks or uncover incongruencies between the formal organisational structure and the de-facto centres of influence within your organisation.

Step 2: EXAMINE the network through a targeted analysis that is specifically designed to deliver the insights you are seeking. For example, you could employ a diagnostic to map communication, collaboration, or trust across your organisation.

Step 3: APPLY the learnings to drive the change you want to see within your organisation, for example, by appointing change leaders, shifting resources to alleviate bottlenecks or bringing teams together to kickstart cross-functional collaboration.

Rather than producing vast quantities of technical information, this flexible approach is designed to deliver actionable learnings. For example, leaders can apply this approach to map trust across their organisation, identify a cohort of influential individuals to act as change leaders or highlight opportunities for enhancing collaboration or improve organisational effectiveness.

References

Diego, G 2017, ‘Are your values actually what you value?’ Right Lane Review, February

Hardy, M & Mills, J 2018, ‘Build and maintain the momentum of strategy execution with quarterly ‘best next steps‘, Right Lane Review, December

Lencioni, P 2002, ‘Make your values mean something’, Harvard Business Review, July

McCrystal, S 2018, ‘Team of Teams’, Penguin Publishing Group, New York

Pappas, Z & Cossens, J 2018, ‘Enhancing effectiveness through improved vertical and horizontal team alignment’, Right Lane Review, December

© 2019 Right Lane Consulting

We hope the ideas presented here have given you something new to think about. We would love the opportunity to discuss them with you in more detail. Get in touch today.