Benefits realisation: from hodgepodge to hierarchy

by Dr Marc Levy & Abhishek Chhikara

Right Thinking

We’ve observed recurring challenges in the way organisations approach benefits realisation: business case writers often propose too many (disconnected) benefits without being able to describe how these benefits will arise. We suggest that organisations adopt a benefits realisation hierarchy; at the top sits the ultimate impact sought by the organisation. Below that is a causal logic demonstrating how the benefits are interrelated. This forms the organisation’s house view on how value is created, and allows for management to contain, sharpen and link benefits.

We see a lot of business cases – for new products and services, new growth strategies, new pricing arrangements. One thing we’ve noticed time and again is a lack of a discipline within organisations when it comes to articulating the benefits of proposed changes. The costs are often consistently and painstakingly described, but the benefits are frequently muddled and piecemeal.

To be fair, benefits realisation is not always straightforward. Benefits are many and varied, and this can give rise to confusion. We find that this is particularly true for non-profit and government clients: deprived of the singularity of the profit motive, what comes first social impact, service performance or economics?

Understand the challenge

It’s not only non-profits and government clients that find articulating benefits hard going. If we were to pile up on a table the scores of business cases we’ve seen in many clients we’ve served, there would be evidence of three problems.

First, there is a laundry list of proposed benefits. Improvement in the customer experience, enhanced service performance, customer satisfaction, productivity improvement, growth in net customer numbers, revenue growth. There’s nothing wrong in proposing multiple benefits, but when a business case contains too many benefits, and the benefits are not explicitly connected, it suggests a lack of a cogent perspective on, and integrated theory of, the benefits of the change being proposed.

Second, benefits are not comprehensively articulated. Net promoter score (NPS) improvement might be listed as a benefit, but not the specific impact that the change is expected to have on the NPS, not the process by which the NPS will be obtained, nor the baseline number that will be used as a reference point, nor the time period of the expected impact.

Third, benefits are described inconsistently. Consistency in how benefits are described across not only projects and programs, but the whole organisation, is critical; otherwise it’s not possible to have an aggregated view on the impacts of (or across) all proposals being made. Customer satisfaction is not the same as customer advocacy or customer loyalty; even within these rubrics there are numerous metrics that can be used to describe intended benefits.

Develop a benefits realisation hierarchy

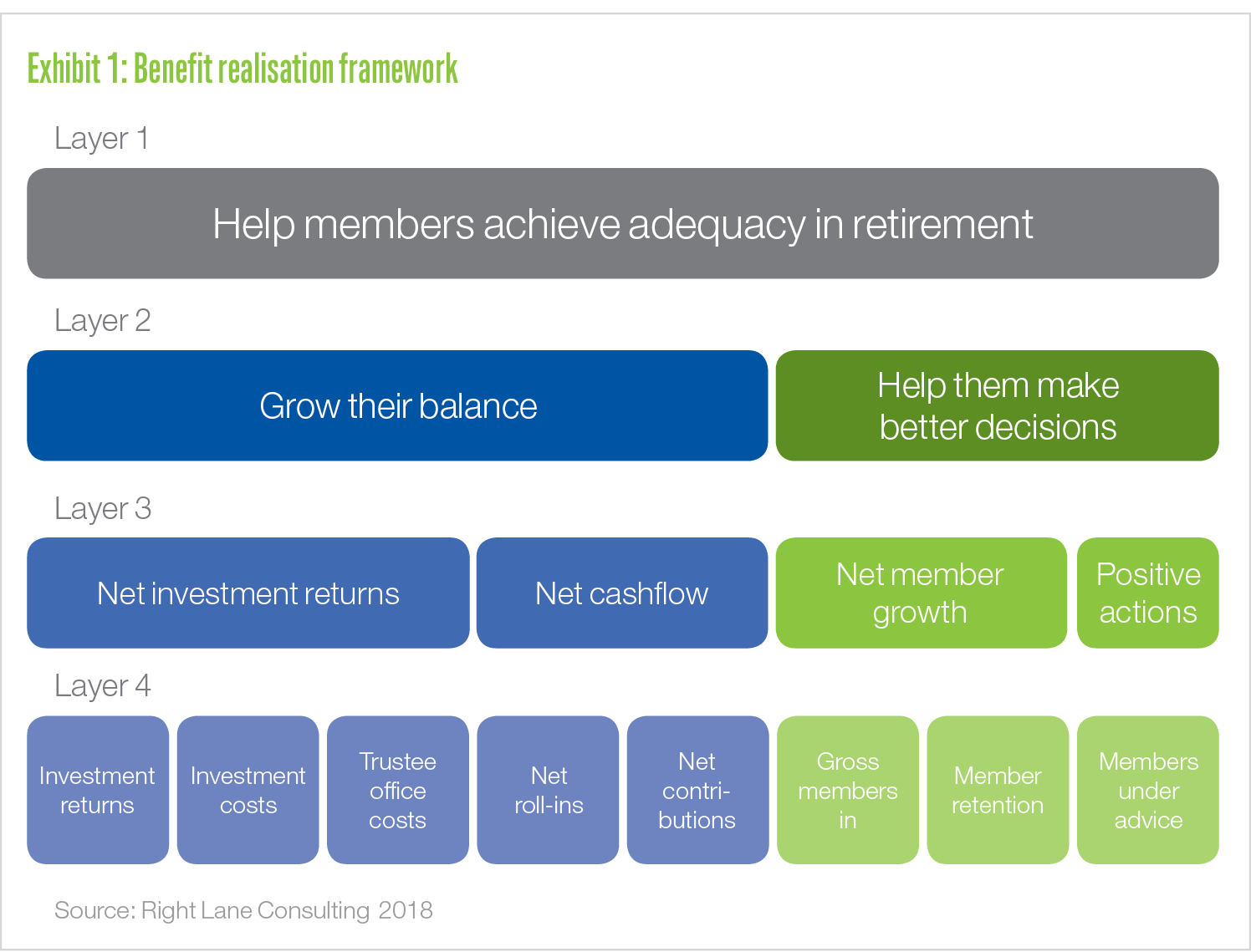

We have a simple approach to resolving these common problems that we call a benefits realisation hierarchy. In the stylised example shown above, a fictitious executive team in the non-profit part of the superannuation industry has sorted benefit ‘tiles’ in to four layers. At the top, the ultimate impact has been defined as helping members achieve adequacy in retirement. Below that is a causal logic that suggests that there are two ways to drive retirement adequacy, growing members balances and helping them make better decisions about their retirement. And so it goes, an architecture of benefit ‘tiles’ that, once agreed, is a ‘house view’ on how value is created within the enterprise.

Set clear guidelines for business case writers

The next step can be as sophisticated or simple as it needs to be to suit the organisation. At the very least the top team should be clear and explicit about the way business cases should engage with the benefits realisation hierarchy; for example, that all business cases should impact one or more level-four tiles in a way that’s demonstrable.

An executive team may decide to take it further and define specific metrics for each of the benefit tiles that business cases must contain. That is, if the benefit impacted by the change is expected to be ‘gross members in’, which in superannuation is an important new business metric, the executive team could mandate that all relevant business cases state the number of gross new members in that are anticipated, and the cost of acquiring new members in the way proposed, and weigh this against the anticipated impacts of other growth strategies and the fund’s overall growth expectations.

Put your benefits realisation hierarchy to work

Business cases must be considered in the context of the alternative application of the capital that may be employed in support of them. They must also be considered in terms of their role among all of the activities that are intended to impact the relevant benefit or benefits and the higher order tiles in the benefits realisation hierarchy.

As we have observed in our work on strategic projects (Levy 2018), organisations are increasingly getting things done through projects, and most projects are born of business cases. Even our midsize clients invest tens of millions of dollars every year in projects and their business cases should more clearly align to an integrated theory of value creation such as the one that has been proposed in this article.

References

Levy, M 2018, ‘Scaffolding strategic projects – giving them the help and support they need’, Right Lane Review, July

© 2018 Right Lane Consulting

We hope the ideas presented here have given you something new to think about. We would love the opportunity to discuss them with you in more detail. Get in touch today.