Bridging the gap between strategy and performance

By Abhishek Chhikara and Debbie Williams

Every year, thousands of Australian organisations undertake strategic planning processes to chart their courses for the coming period. Frequently executives set ambitious long term objectives and targets, as well as detailed initiatives for the next year. Year one targets are often based on what is considered achievable, and the step change growth required to deliver the long-term target is forecast for subsequent years. Year one targets are easily delivered; the process is repeated. However, if this continues each year without commitment to step change in the upcoming period, it can lead to significant underperformance against long-term goals.

To bridge this gap between strategy and performance, we suggest organisations should adopt the following four practises in their strategic planning processes:

- Vigorously debate underlying assumptions

- Articulate strategic initiatives beyond the next twelve months

- Be prepared to correct course

- Align the organisation with the long term strategy.

Every year, thousands of Australian organisations embark on strategic planning processes to agree crucial objectives and plan how they’re going to achieve them. This top down approach starts with the destination, and then charts the journey (initiatives) required to get there. However, unlike travel plans, which have defined routes and set destinations, it is easier for organisations to stray off course. Staying on track requires careful planning and constant adjustment.

In Strategy Mapping, Kaplan and Norton (2004) popularised the idea of ‘mapping’ an organisation’s strategy by linking strategic objectives, the attendant measures of success, and the initiatives required to drive performance. This was intended to provide employees with a clear line of sight, to remove ambiguity regarding how their roles link to the overall objectives of the organisation, and to convert the organisation’s initiatives and resource allocations into tangible outcomes. However, this is easier said than done.

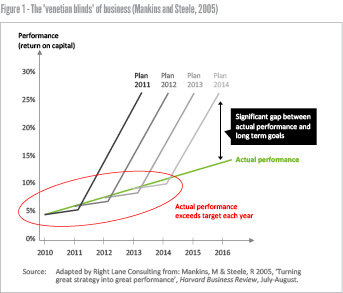

In our experience, executives often set ambitious medium to long term ‘top down’ objectives, but only plan initiatives for the first year based on what is known to be achievable. This leaves the bulk of the growth in subsequent periods from undefined sources. Having met the achievable year one targets, the temptation is to once again plan the next year’s initiatives based on the current situation, in effect pushing out any step change growth for another year. This pattern, if repeated year after year, has been referred to as the ‘venetian blinds’ of business (Mankins and Steele, 2005 – see Figure 1). Annual targets are often then exceeded, but in the long term the organisation falls short of its long term strategic objectives.

To bridge this gap between strategy and performance, we suggest organisations should adopt the following four practises in their strategic planning processes.

1. Vigorously debate underlying assumptions

Assumptions are a necessary part of a strategic planning process. Many organisations depend largely on their senior management’s knowledge and insights to form assumptions rather than conducting field tests. Failing to market test assumptions creates the risk of derailing the organisation’s strategy. To develop robust assumptions, organisation should:

Be realistic: Reviewing past performance and the underlying assumptions can uncover insights about the fundamental causes of an organisation’s failure to deliver on its plan.

Conduct structured experiments: Large organisations can benefit from the ‘fail often, fail quickly’ mindset of agile start-ups. Conducting structured experiments can help to understand what works and what does not, and validate or disprove critical assumptions.

Introduce different thinking: Once the strategy is set, it is critical to maintain a culture of challenging and testing assumptions, allowing the organisation to correct its course where needed. Levy (2017) suggests introducing ‘heretical thinking’, through a thought provoking article, an unconventional external speaker or a challenging ‘fact pack’, to encourage reexamination and reassessment of assumptions.

2. Articulate strategic initiatives beyond the next twelve months

Strategic initiatives are where the ‘rubber hits the road’ in strategic planning. Yet it is common for executives’ efforts to falter when charged with developing detailed plans for the ‘out years’. Executives rush to set measures and targets, yet fail to do the proper planning to understand the likely impact of the initiatives on long term performance.

To develop more useful initiative plans, organisations should:

Be specific: We recommend being granular about each initiative, defining precise scope of work, considering the actions that support the initiative by year (including the out years).

Evaluate the impact: The impact an initiative will have can be hard to quantify and can be contested. However, the ultimate measure of success for an initiative is generally its positive financial impact. We suggest building a multi-year profit and loss statement for each initiative, and linking these to the organisations underlying ‘base case’ financial forecasts and targets, allowing the organisation to closely and more holistically monitor progress.

Discuss resource allocation: Mankins and Steele (2005) suggest discussing resource deployments early in the strategic planning process to create realistic longitudinal forecasts and plans that are achievable. These resourcing discussions allow executives to make informed decisions when agreeing initiatives and improve the overall quality of the strategic plans. Once plans are agreed, the actual resource deployment should be monitored regularly to ensure things are on track.

3. Be prepared to correct course

No strategic plan can predict every event that may occur and organisations should be prepared to make real-time adjustments to ‘correct their course’.

To build this flexibility into their strategic process, organisations should:

Monitor constantly: Kaplan and Norton (1996) introduced balanced scorecards, which revolutionised how strategy was monitored. Scorecards are useful tools, allowing organisations to monitor their performance, as well as communicate their successes. In addition, visual metrics can be used to create energy within the organisation and provide teams with an early indication of what is working or not working (Spiteri 2013).

Review frequently: Organisations should consider implementing a regular strategy review process that allows executives to reflect both internally and externally, and make informed decisions to mitigate strategic risk and leverage strategic opportunities. The review should cover performance against the targets and with the initiatives, and topical discussions that are germane to the organisation’s strategy.

These practices should enable executives to better understand the true causes of high performance and mitigate the need for uninformed recasting of annual targets.

4. Align the organisation with the long-term strategy

Break through growth requires the whole organisation’s focus on the long term goal rather than day-to-day tactics. To generate alignment and buy-in organisations should:

Demonstrate strong and consistent leadership: The development of strategy should be led the by the CEO and supported by senior management. Where possible they should link their actions and messages to strategic objectives and remain committed to the same strategic frameworks and approaches throughout a strategic planning cycle. This gives employees a consistent and reliable frame of reference. The leadership also needs to be prepared to challenge the status quo and make tough calls, even when performance is ok, if ‘ok’ is not good enough to reach the objectives.

Translate the strategy into day-to-day: Organisations can benefit from providing clear links between an employee’s role or position description, and their personal objectives, and the overall strategic objectives. Ensuring employees are aware of how their role and performance contribute to the organisation’s strategy is, in our experience, more motivating and allows them to better prioritise and plan their work over time.

Engaging the organisation in your next strategic planning process will help to ensure that your strategy is well considered and has a better chance of impacting performance in the way you intended.

***

Implementing these four practices will help your organisation bridge the gap between strategy and performance, and in doing so give it a more realistic chance of meeting long term objectives and targets.

References

Kaplan, R, & Norton, D 1996, The balanced scorecard: translating strategy into action, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Kaplan, R, & Norton, D 2004, Strategy Maps: Converting intangible assets into tangible outcomes, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Levy, M 2017 ‘Balancing conviction and flexibility: a roadmap for testing and challenging strategy’, Right Lane Review, February.

Mankins, M & Steele, R 2005, ‘Turning great strategy into great performance’, Harvard Business Review, July-August.

Spiteri, L 2013 ‘Seeing is believing: visual metrics displays’, Right Lane Review, December.

© 2017 Right Lane Consulting