Do more with less by borrowing from agile practices

by Zoe Pappas and Richard Waid

Right Thinking

Applying agile practices to traditional business problems is straight-forward and may present meaningful advantages over other approaches – greater efficiency, helping people work better together, and building team capability and project momentum. In this article, we share how you can use agile practices to get more done in your strategic projects with less effort, and we bring this theory to life by demonstrating how we’ve done this in practice on a recent client engagement.

Project approaches are under the spotlight

2020 was indeed a year of paradigm shifts. The health, political and economic implications of the COVID pandemic wreaked change on organisations in manifold ways. Many still face an environment of constrained revenue, putting pressure on budgets, resourcing and investment.

In parallel, many organisations are dealing with transformative efforts on multiple fronts:

- rapidly developing new strategies to handle changes in short- and long-term demand

- building the enabling infrastructure to facilitate new ways of working and more customers transacting and engaging online

- stripping out costs to preserve profitability.

New words entered the business lexicon – ‘pivot’ for example, and ‘COVID-normal’. Oh agile, dear old friend, you now seem so 2010!

And yet, there may never have been a better time to consider how agile principles can help us rethink the way we deliver strategic projects in the context of this new environment.

Managers are facing pressure to do more with less

We’ve heard from many of our clients that executives and managers have lists of strategic projects that have stalled. Executing these projects using traditional ‘waterfall’ approaches may no longer be fit-for-purpose. This approach often requires planning horizons, and resourcing commitments, over timeframes that are too long to contemplate under current levels of uncertainty.

In many instances, executives must find ways to get more done with a shrinking resources base, or where demand expectations are uncertain, yet where standing still could ultimately lead to failure.

Organisations can improve the productivity and pace of their strategic projects by applying agile concepts. Adopting these principles reflects a simple change in how projects are planned and executed, and the concepts are accessible and applicable to many different organisations and contexts.

Agile project methodology represents a simple shift in planning priorities

First though, let’s talk a bit about what we mean by agile principles. The term ‘agile’ comes originally from software developers in the early 2000s and was designed to provide software engineers with an alternative to the traditional ‘waterfall’ approach to project management. However, as the term has become woven into business parlance, it’s taken on different meanings to different people. We’ve written previously about how organisations can adopt agile resource allocation practices to improve their effectiveness (Levy, 2019); and more broadly about 3 agility levers (agile strategy, ways of working and resources) that organisations can adopt to create value (Hardy & Levy, 2014).

First though, let’s talk a bit about what we mean by agile principles. The term ‘agile’ comes originally from software developers in the early 2000s and was designed to provide software engineers with an alternative to the traditional ‘waterfall’ approach to project management. However, as the term has become woven into business parlance, it’s taken on different meanings to different people. We’ve written previously about how organisations can adopt agile resource allocation practices to improve their effectiveness (Levy, 2019); and more broadly about 3 agility levers (agile strategy, ways of working and resources) that organisations can adopt to create value (Hardy & Levy, 2014).

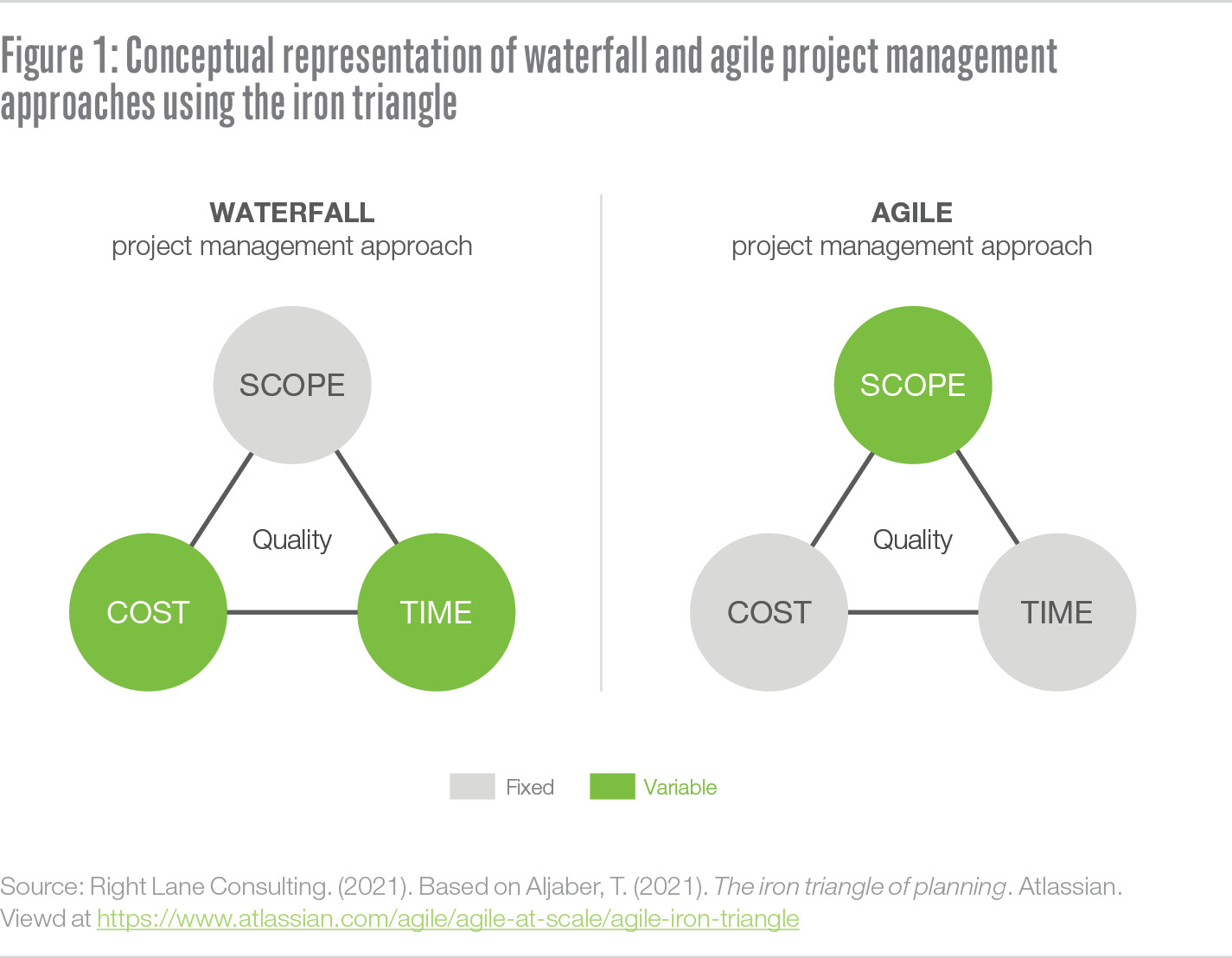

In the context of strategic projects: agile represents a shift in how projects are planned and managed. While waterfall methodologies plan activities sequentially, around a fixed outcome, agile methodologies plan activities iteratively, around a fixed set of resources (e.g. time, people). This concept is represented with reference to the ‘iron triangle’ of project management. Traditional waterfall projects typically work to a fixed outcome (scope and quality) and will flex the resources and time needed to achieve that outcome. Agile projects typically have a fixed resource pool and timeline, and will iteratively develop outcomes (and by extension scope) aligned to this.

Applying agile disciplines in practice

We’ve distilled lessons from conducting hundreds of projects over recent years and identified 4 simple building blocks that organisations can adopt to do more with less, drawing on agile methodology and consulting disciplines. We outline these building blocks below with reference to a recent project we delivered for a government agency client.

Building block 1: Form small, multi-disciplinary teams to do the work

There is a wealth of research and commentary on why small, multi-disciplinary teams excel at solving complex strategic problems, and are preferable to large teams in this context.

In a recent engagement, our client was hungry to collaborate, and the challenge we helped them with was one that touched many stakeholders. Those with the most to contribute (in terms of expertise, time and enthusiasm) were formed into smaller cross-functional workstream teams. Roles were defined using a RASCI matrix (that is: defining who is Responsible, Accountable, Supporting, Consulted, and Informed), including for executive- and leadership team-level sponsors to build appropriate buy-in and manage barriers.

Building block 2: Deploy teams in sprints with a fixed time horizon (e.g. 6-10 weeks) and coach them on new ways of working

We established a sprint process with 4 steps. The first step was to form the sprint teams, working with members to confirm the scope of the sprint, develop detailed workplans, clarify roles and responsibilities, and agree ways of working. The second step was to execute the sprint workplans (as defined in the first step). The third step was to implement recommendations from the sprints (which varied based on the nature of work undertaken). The fourth and final step was to debrief and disband the sprint, eliciting and codifying any lessons/reflections they had on the process and applying this in the next iteration of sprints.

In the case of our client, the sprints were organised around a 6-week timeline, with a week either side for planning and documentation. Within the sprints, tasks were managed in 2-week blocks so that draft deliverables could be completed, tested and iterated by the sprint team in short, intense bursts.

We helped teams establish their ways of working to manage their time and work effectively during sprints. The sprints took place during Melbourne’s lockdown, meaning all teams were working virtually and remotely. So, we encouraged them to:

- establish channels for each workstream using their digital collaboration platform (in their case, Microsoft Teams) for frequent, real-time communication, for saving shared files and collaborating on deliverables

- establish an appropriate operating rhythm (weekly or bi-weekly team huddles, plus more formal check in points with sponsors and the core organising team who were coordinating the sprints)

- make use of tools like the virtual Kanban board and whiteboard functions attached to Microsoft Teams to share team priorities and track workflows.

The workstream teams were energised by the pace and the ability to experiment with different ways of working outside their normal operations.

Building block 3: Organise Sprints using a structured problem-solving approach

Rather than just let the teams loose at the problem, we set them up for success by running a series of structured problem-solving sessions. Through this approach, each team was supported to create the ‘problem’ or opportunity statement that clearly defined the essence of the issue they were seeking to address.

We then applied ‘bulletproof problem solving’ (Conn & McLean, 2019) techniques to: help teams break their problem down into a series of sub-questions; prioritise and sequence the sub-questions to be tackled by the teams in 3 time horizons (now, next, later); develop a workplan to address each priority sub-question; and clearly define deliverables for each question.

Of course, once the sprints were underway, the teams had some flexibility to iterate their workplans as further data and insights emerged. But the discipline of having articulated the sub-questions to be tackled in 3 time-horizons (now, next, later) meant teams kept coming back to the specific question they sought to address, and were confident that other questions would be addressed later in the process. This helped the teams manage ‘scope creep’ by not trying to do everything at once.

Building block 4: Take a hypothesis-driven approach to addressing issues

A hypothesis-driven approach to problem solving, rather than a data-driven approach, helps teams to focus their analysis of the problem and direct the efforts of team members.

We encouraged the sprint teams to get started by forming hypothesised answers to the sub-questions they addressed in their sprint. By forming hypotheses, data gathering efforts were targeted and focused on sourcing the relevant facts to test these hypotheses. This approach drives efficiency by cutting out unnecessary data gathering and analysis (which is typically a large component of strategic projects). And it drives clarity through its logic and structure. Using this method, the final audience only sees the evidence directly relating to the project hypotheses, without wading through reams of analysis that was later deemed irrelevant to the problem at hand.

By applying these 4 building blocks, based on agile principles, teams can unlock effectiveness and do more with less.

CASE STUDY – Agile practices in action

OVERVIEW

Our client – a state government owned statutory authority – wanted support to adopt agile practices to tackle their ongoing strategic projects. Specifically, they wanted to:

- achieve their objectives faster

- use less of their teams’ time

- embed an engaging, collaborative and an achievable way of working to support project delivery over the long-term.

Fast, efficient, collaborative and engaging project delivery – it seems too good to be true!

APPROACH

Working with our client, we mobilised ~25 people into 4 teams, deploying each team in 6-week sprints. Each sprint addressed a distinct business problem, and had a clear workplan and set of deliverables to achieve within the timeframe. During the sprint, Right Lane helped scaffold collaboration between the teams, executives, and the broader business – building buy-in for this work and progressing the probelm-solving within each sprint.

We knew it was important to help the teams establish new ways of working. The pace and style of work in a sprint was novel for those involved, and the broader business – so, we guided each team through a series of structured problem-solving sessions. During these sessions, we applied ‘bulletproof problem solving’ (Conn & McLean, 2019) techniques to:

- create ‘problem’ or opportunity statements that define the essence of the issue they were seeking to address

- help teams break their problem down into a series of sub-questions

- prioritise and sequence the sub-questions to be addressed by the teams in 3 time horizons (now, next, later)

- develop hypotheses about what we believe the solution is to these issues

- develop a workplan to address each priority sub-question

- clearly define deliverables for each question.

Sprint teams had flexibility to iterate their workplans as new data and insights emerged. But the discipline of anchoring the workplan around sub-questions and hypotheses meant teams stayed focused on immediate priorities, and felt confident other questions would be addressed later in the process.

We encouraged sprint teams to maintain a hypothesis-led approach. This meant data-garthering and analysis efforts were targeted on sourcing only the relevant facts/insights to test these hypotheses. This drives efficiency by cutting out unnecessary data gathering and analysis (typically a large component of strategic projects). And it drives clarity through its logic and structure. Using this method, the final audience only saw evidence (that is: slides and charts) directly relating to the project hypotheses, without wading through reams of analysis that was later deemed irrelevant to the problem at hand.

RESULTS

To understand how the sprint approach helped our client, we surveyed those involved and found that:

- 80% agreed it enabled efficient delivery of their projects

- 93% agreed it improved and facilitated collaboration between business groups

- 87% agreed it created clarity on the roles and responsibilities of team members.

Reflections from Sprint team participants:

‘Everyone has been willing to challenge our traditional thinking and to put a whole new lens over this project .

‘I was so pleasantly surprised – we came up with concepts [in the sprints] that I don’t think individually we could have come up with if we were all working separately.’

References

Aljaber, T. (2021). The iron triangle of planning. Atlassian. https://www.atlassian.com/agile/agile-at-scale/agile-iron-triangle

Conn, C., & McLean, R. (2019). Bulletproof problem solving: The one skill that changes everything. Wiley.

Hardy, M., & Levy, M. (2014, April). Organisational agility – how to knock down structures that are limiting your organisation’s effectiveness. https://www.rightlane.com.au/organisational-agility/

Levy, M. (2019, December). Three practices of agile resource allocators. https://www.rightlane.com.au/three-practices-of-agile-resource-allocators/

We hope the ideas presented here have given you something new to think about. We would love the opportunity to discuss them with you in more detail. Get in touch today.